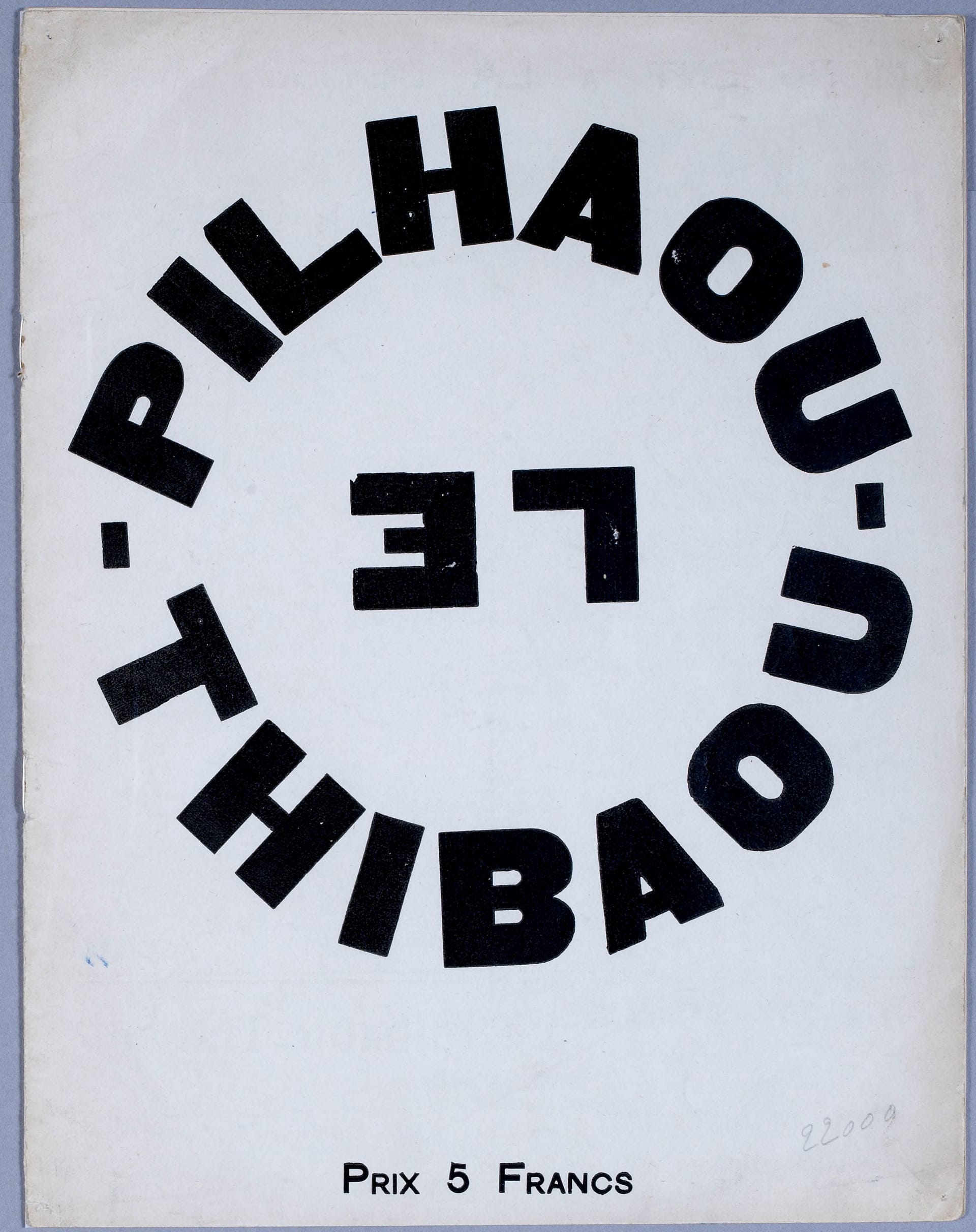

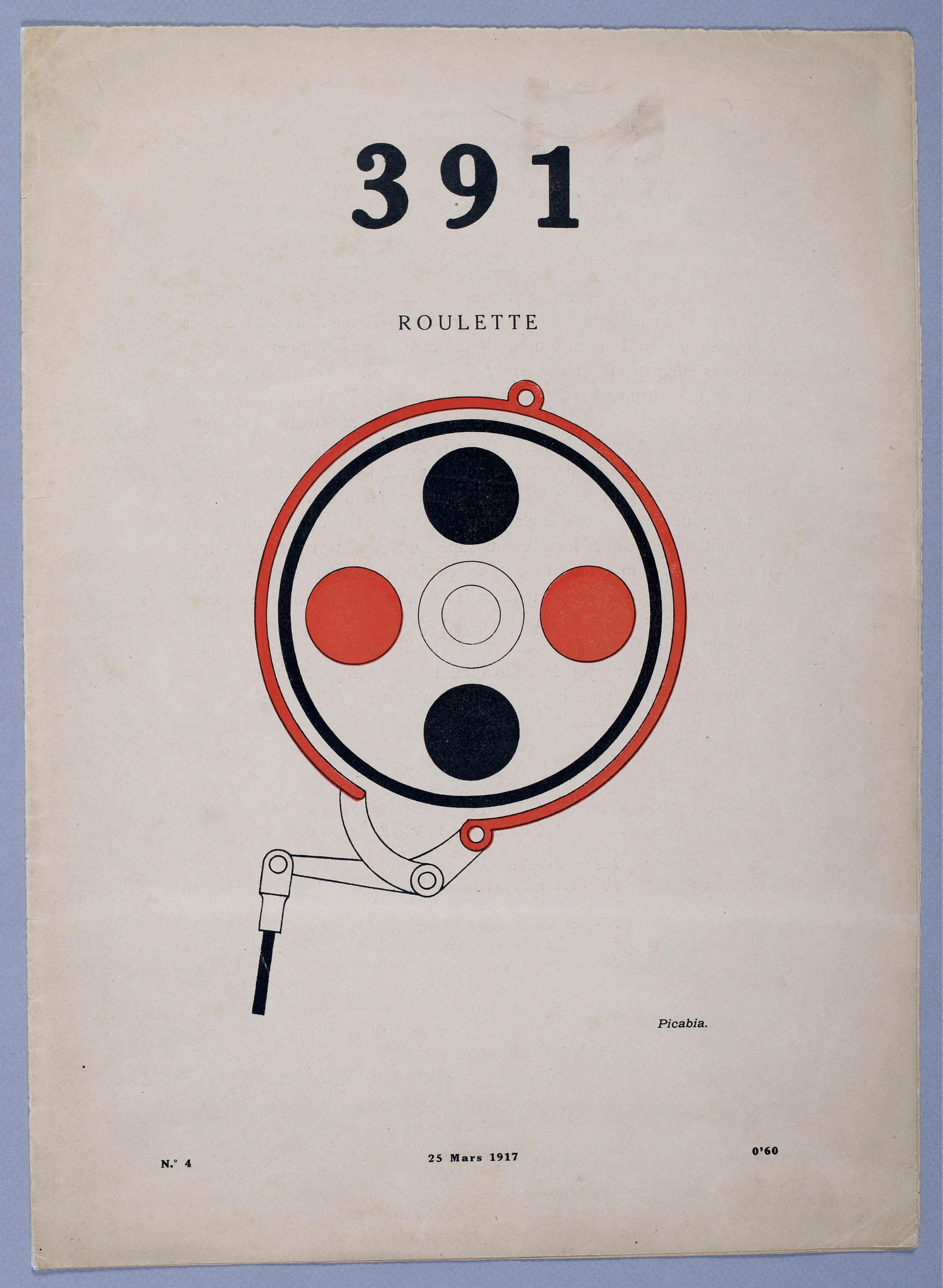

Founded in 1917 in Barcelona during Francis Picabia’s voluntary exile from World War I, 391 emerged as one of the most provocative and conceptually daring periodicals of the European avant-garde. Its title echoed Alfred Stieglitz’s 291—the New York magazine and gallery where Picabia had previously collaborated—thereby establishing a symbolic bridge between the American and European modernist scenes.

From its inception, 391 was conceived as a nomadic publication. Each issue appeared in a different city—Barcelona, New York, Zurich, and Paris—mirroring the restless, cosmopolitan ethos of Dada. Nineteen issues were ultimately published, all under Picabia’s near-total control. He frequently signed texts written by others, used pseudonyms, and blurred the boundaries between editor, author, and performer.

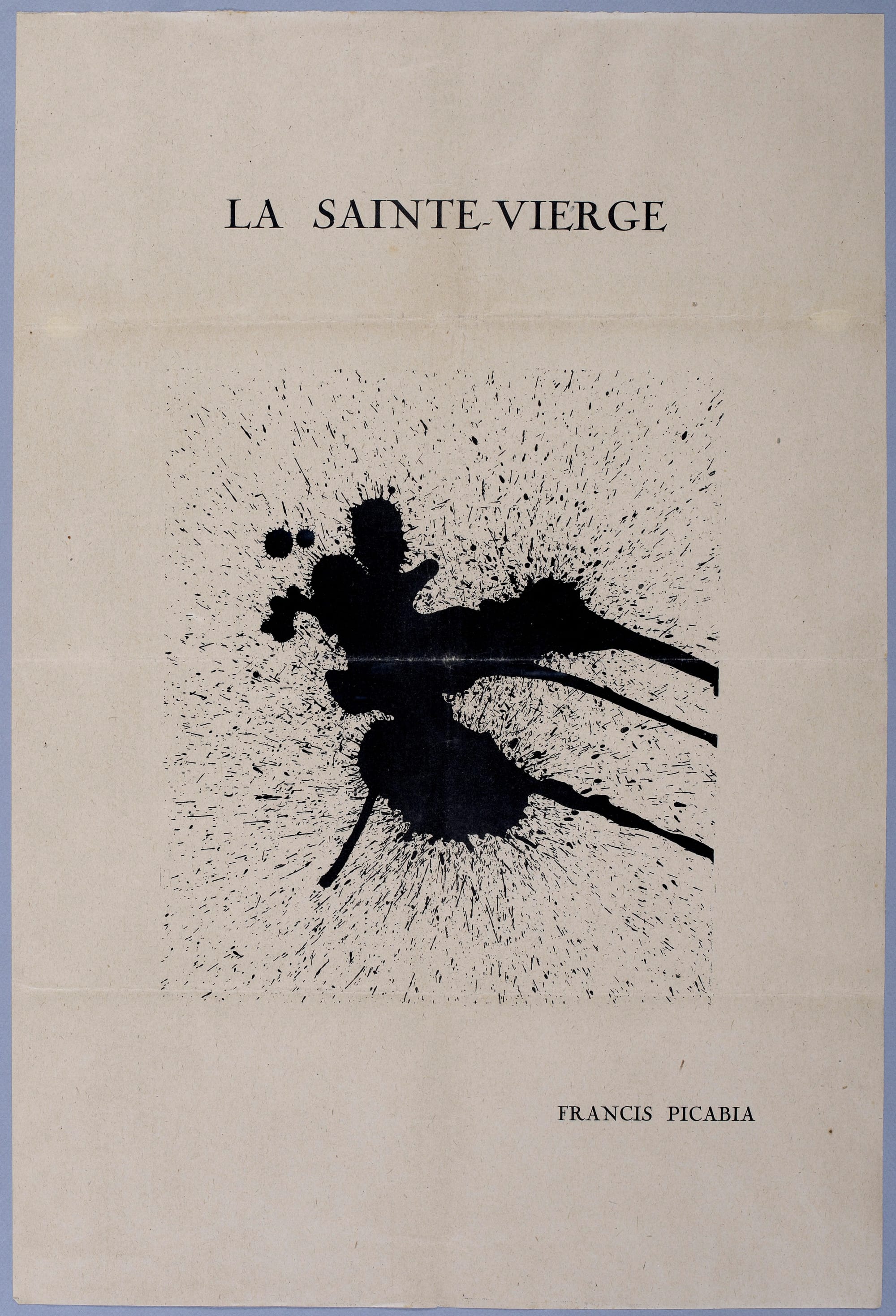

The magazine fused manifestos, absurd poems, collages, typographic experiments, and virulent attacks against academicism and bourgeois taste. Far from being a regular or coherent publication, 391 was a series of singular objects—each issue functioning as an autonomous artistic event, almost a printed performance.

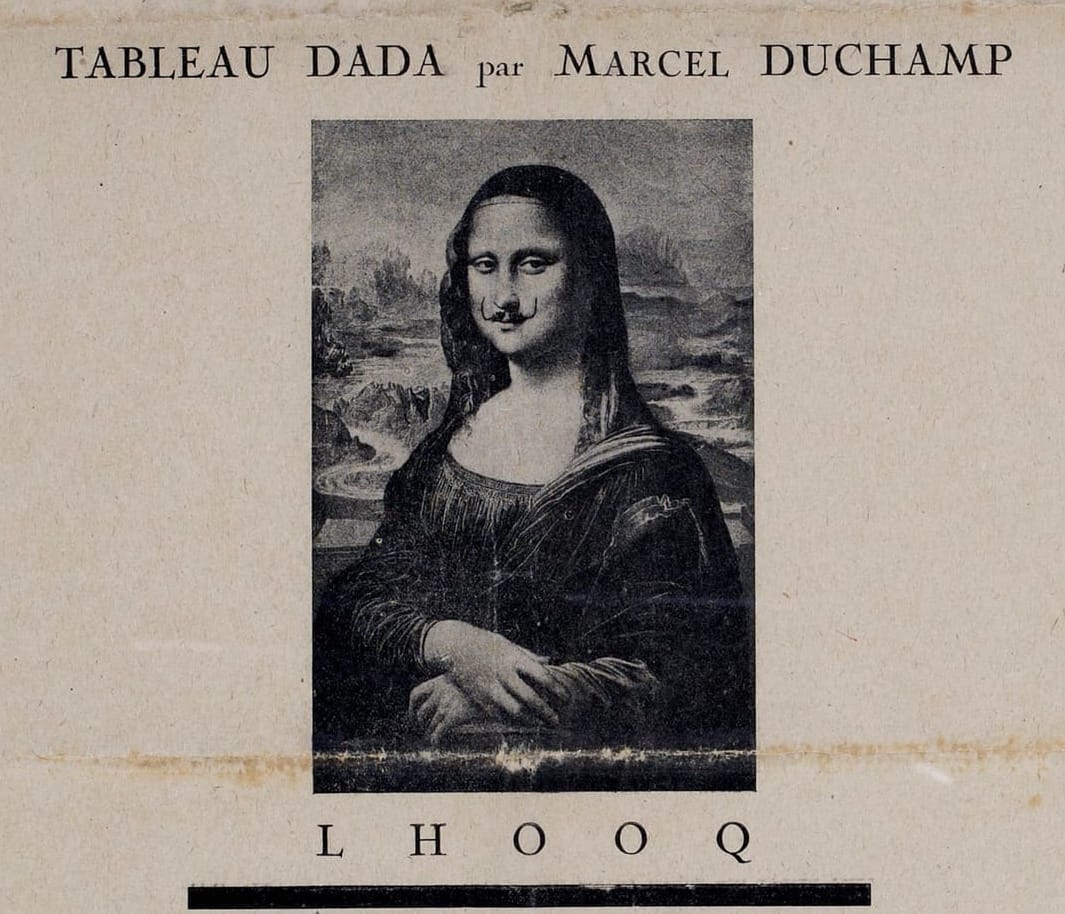

A constellation of key figures in the avant-garde appeared in its pages: Tristan Tzara, the leader of Zurich Dada; Marcel Duchamp, Picabia’s close friend and accomplice; Man Ray, Guillaume Apollinaire, Robert Desnos, Georges Ribemont-Dessaignes, and André Breton—before the founding of Surrealism.

In its later issues, 391 turned increasingly polemical, featuring Picabia’s biting critiques of Breton and the nascent Surrealist movement. His dispute with Breton became a symbolic confrontation between absolute artistic freedom and the emerging orthodoxy of Surrealism. Within 391, parody became a weapon: Picabia mocked manifestos, solemn declarations, and every attempt to institutionalize the avant-garde.

The magazine ceased publication in 1924—the same year as Breton’s First Surrealist Manifesto—as if its final issue were an ironic farewell to the Dada spirit. Picabia’s satire foreshadowed Surrealism’s later self-critique, when Breton himself would be accused of authoritarianism by members of his own circle.

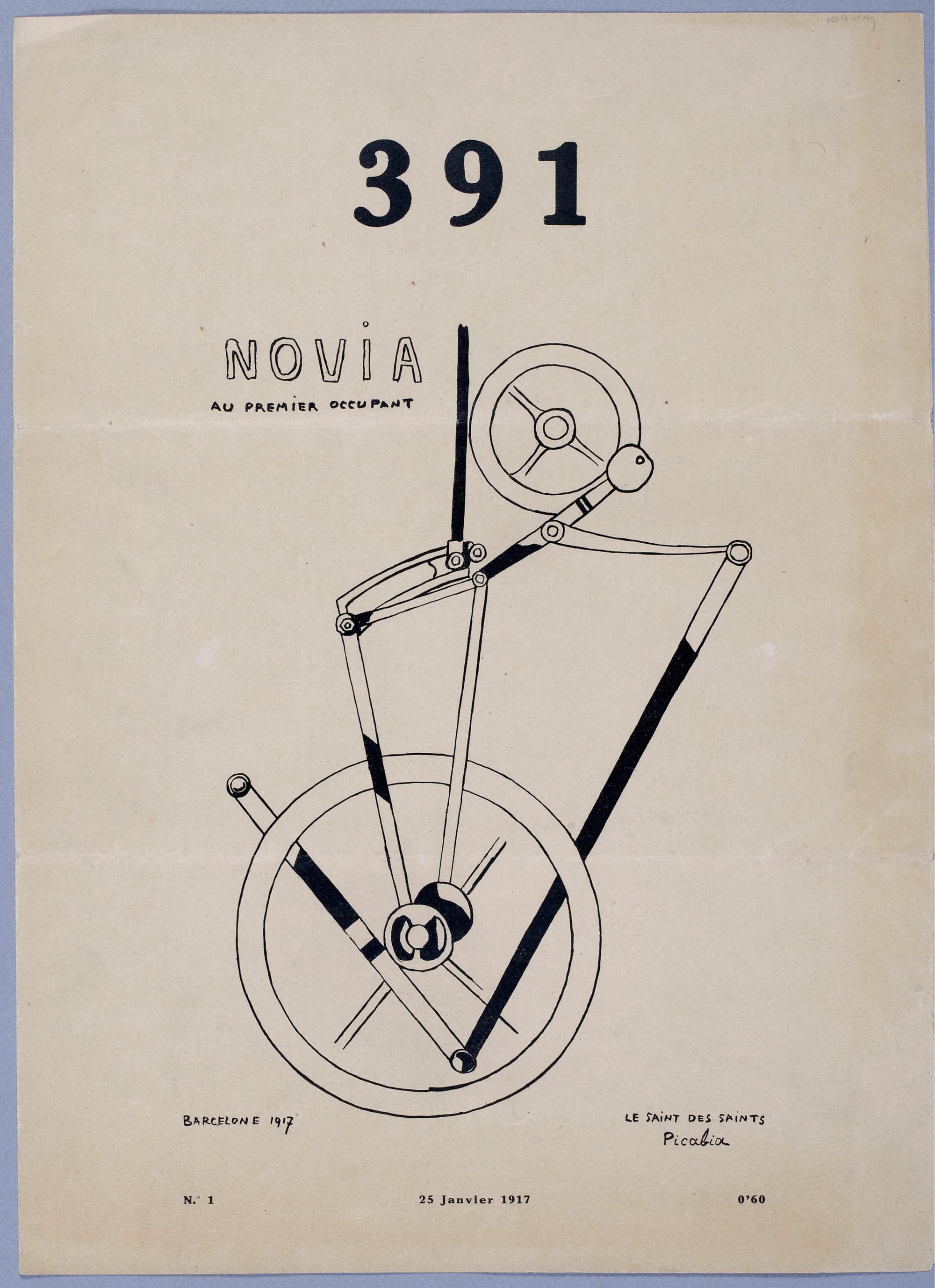

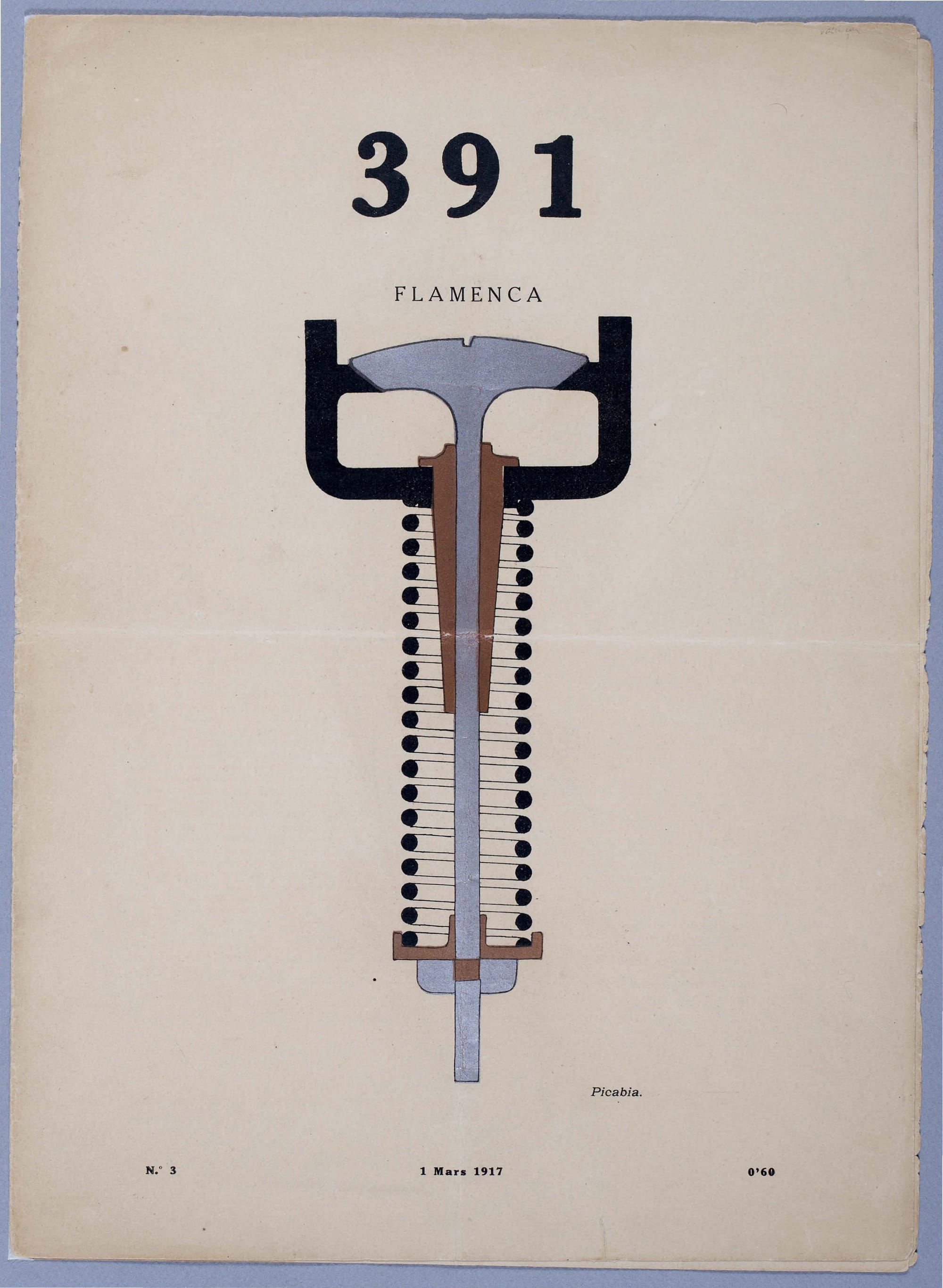

Mechanical Icons of 391

From machines to abstract irony, these covers by Francis Picabia shaped the visual identity of 391.

See the complete selection and designs inspired by these works in our shop

If you enjoy Zehnlicht’s curated work, you can support the project by subscribing (from US$1) or with a one-time donation.

Your support keeps the site independent and ad-free.