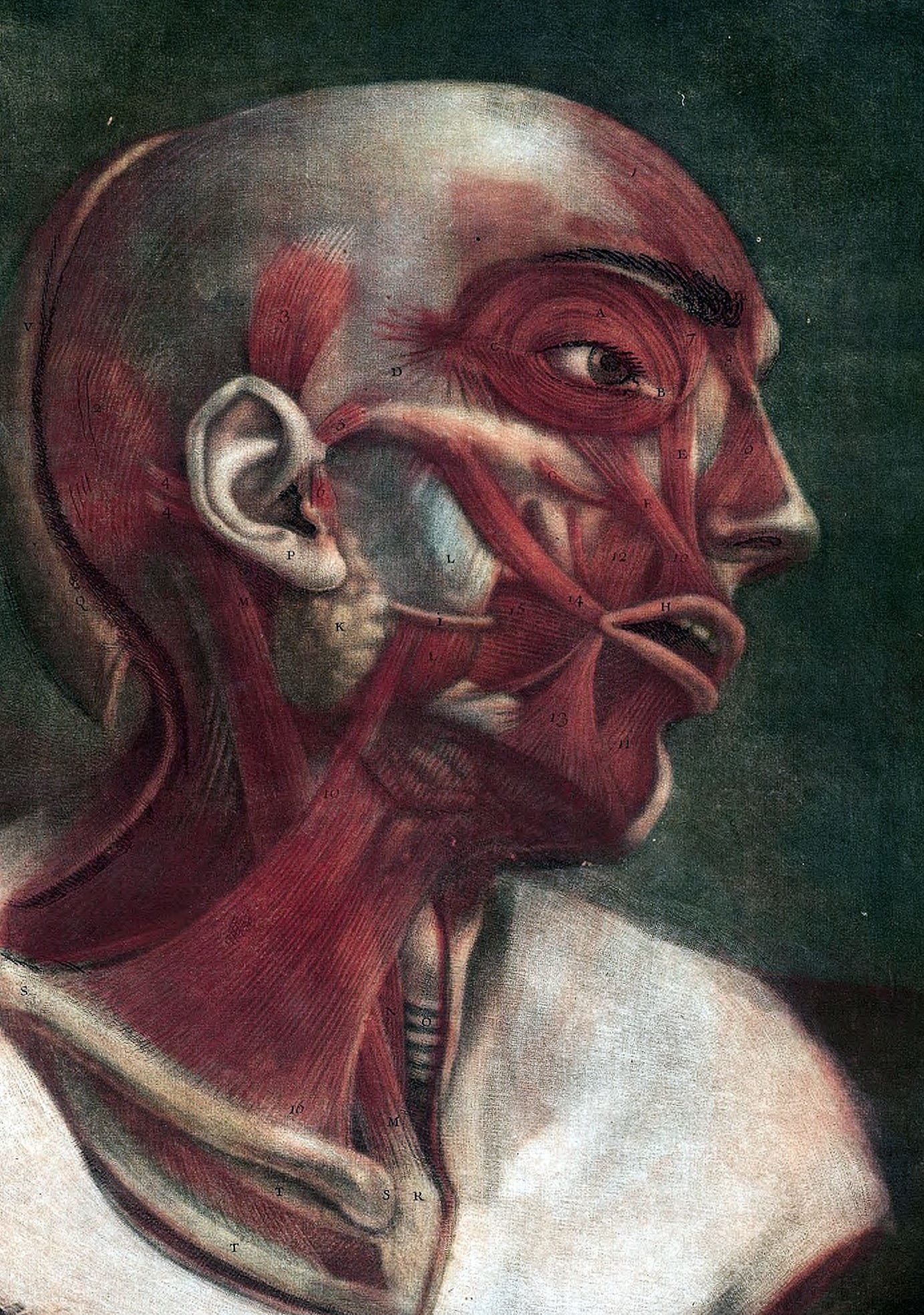

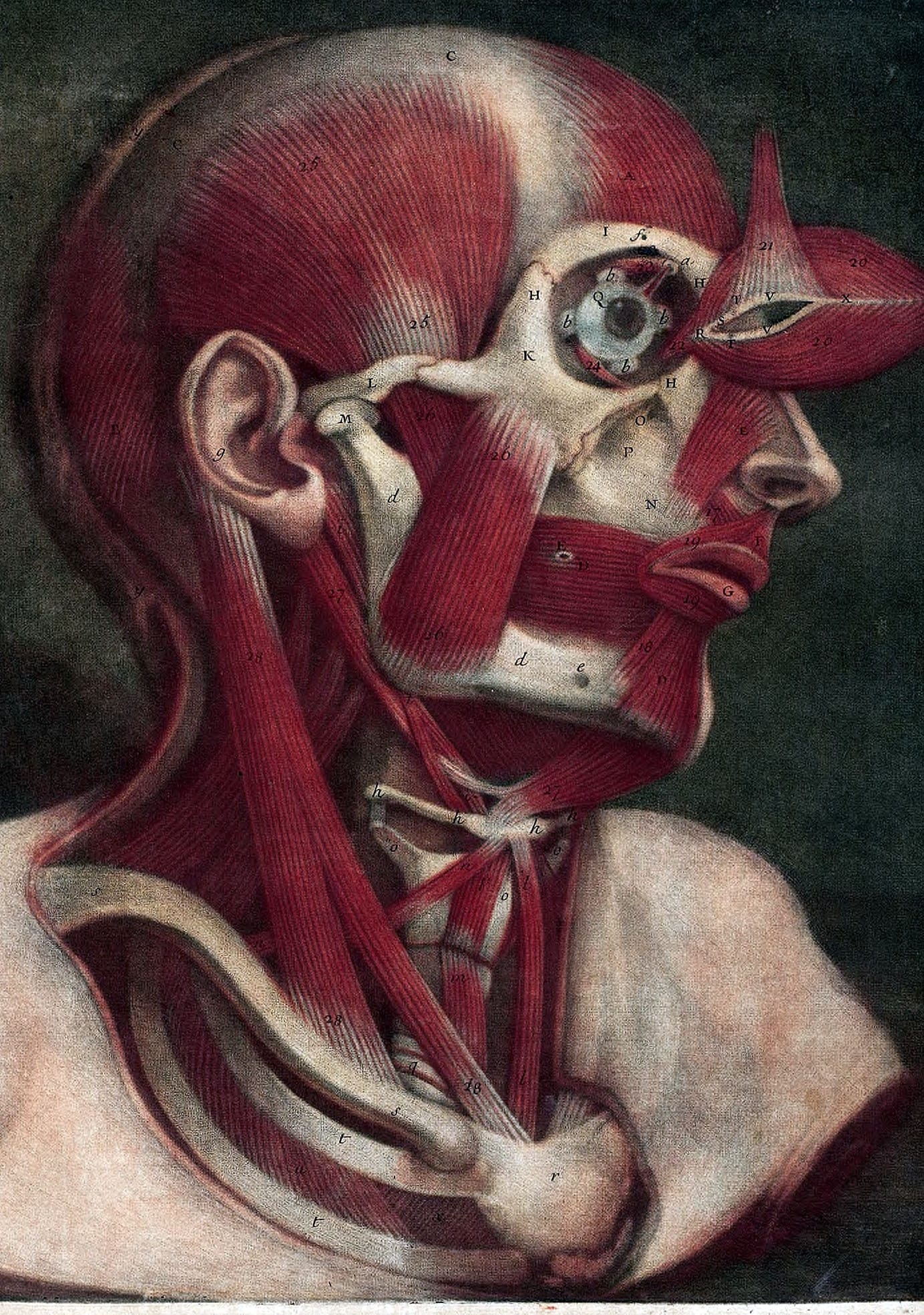

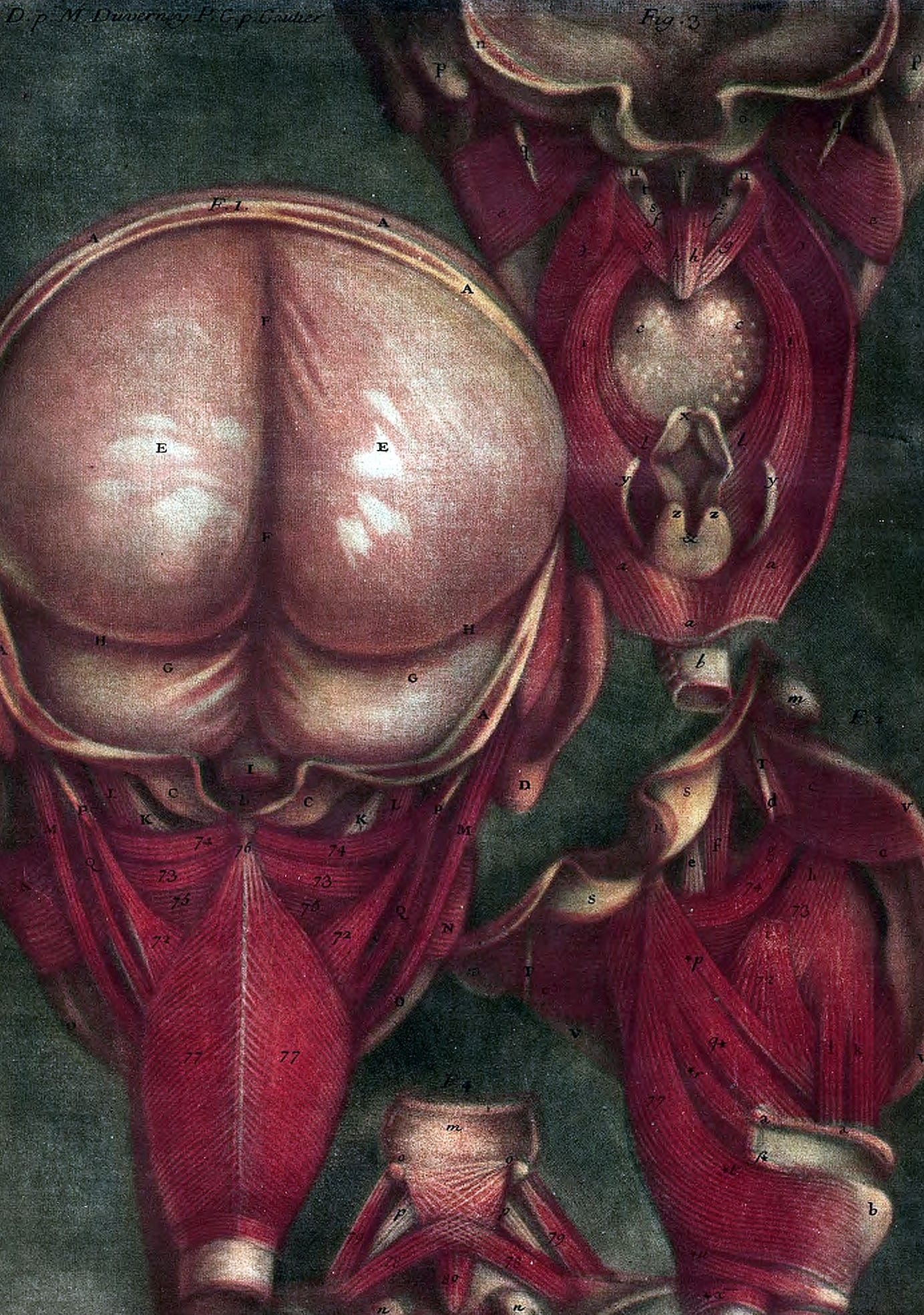

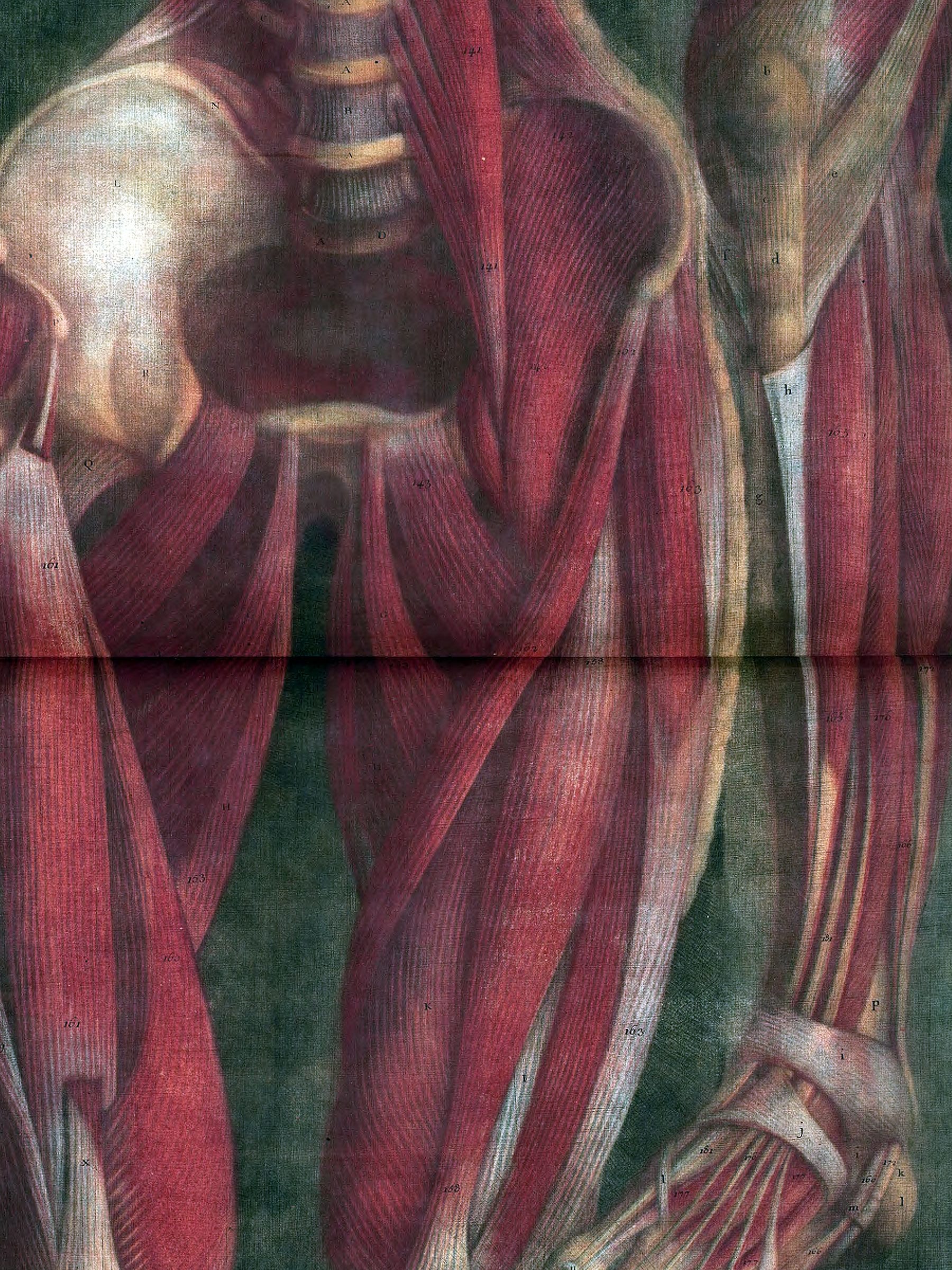

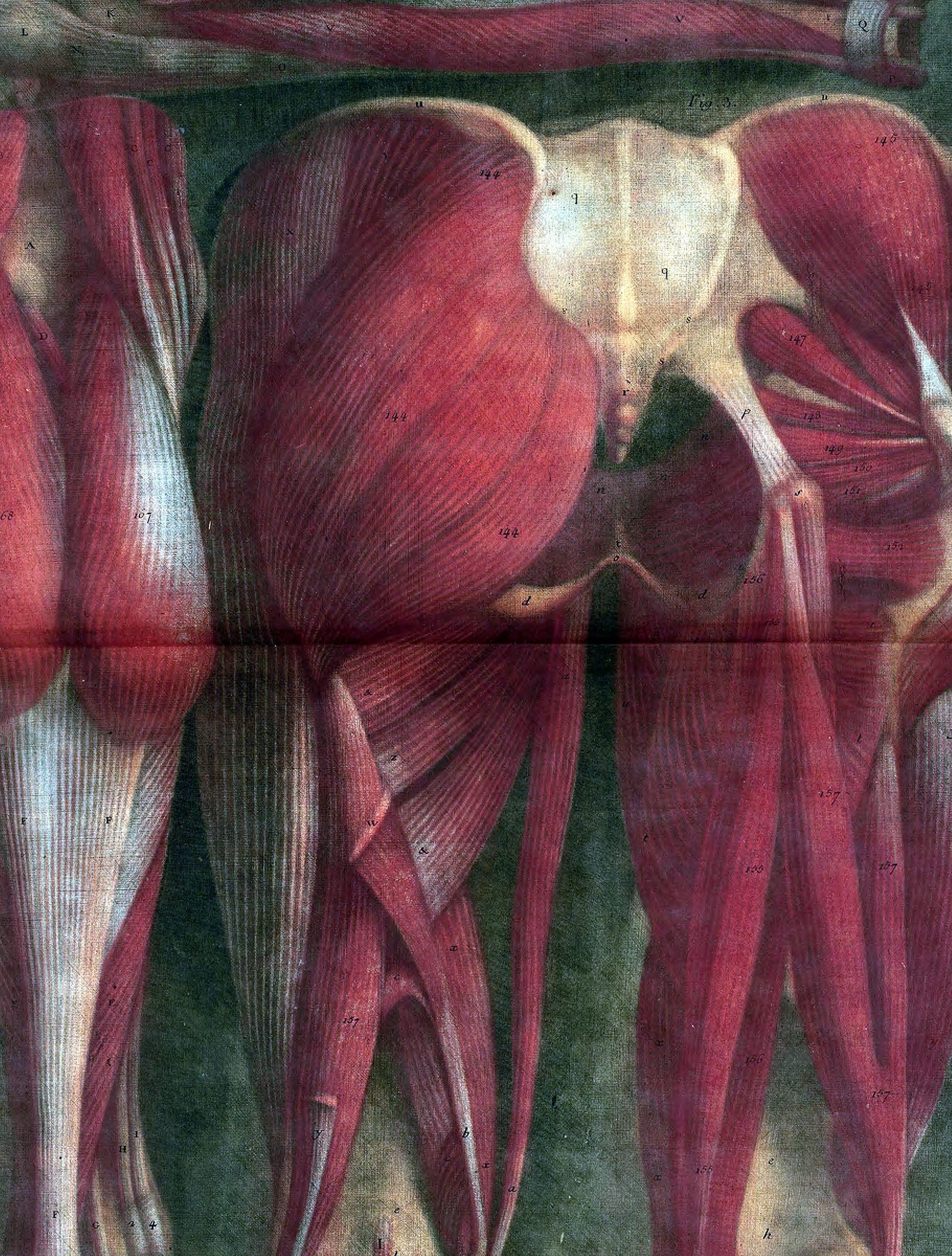

Myologie complète en couleur et grandeur naturelle (1746) – Gautier d’Agoty’s most famous work, featuring full-color anatomical illustrations of the human muscular system reproduced at life size.

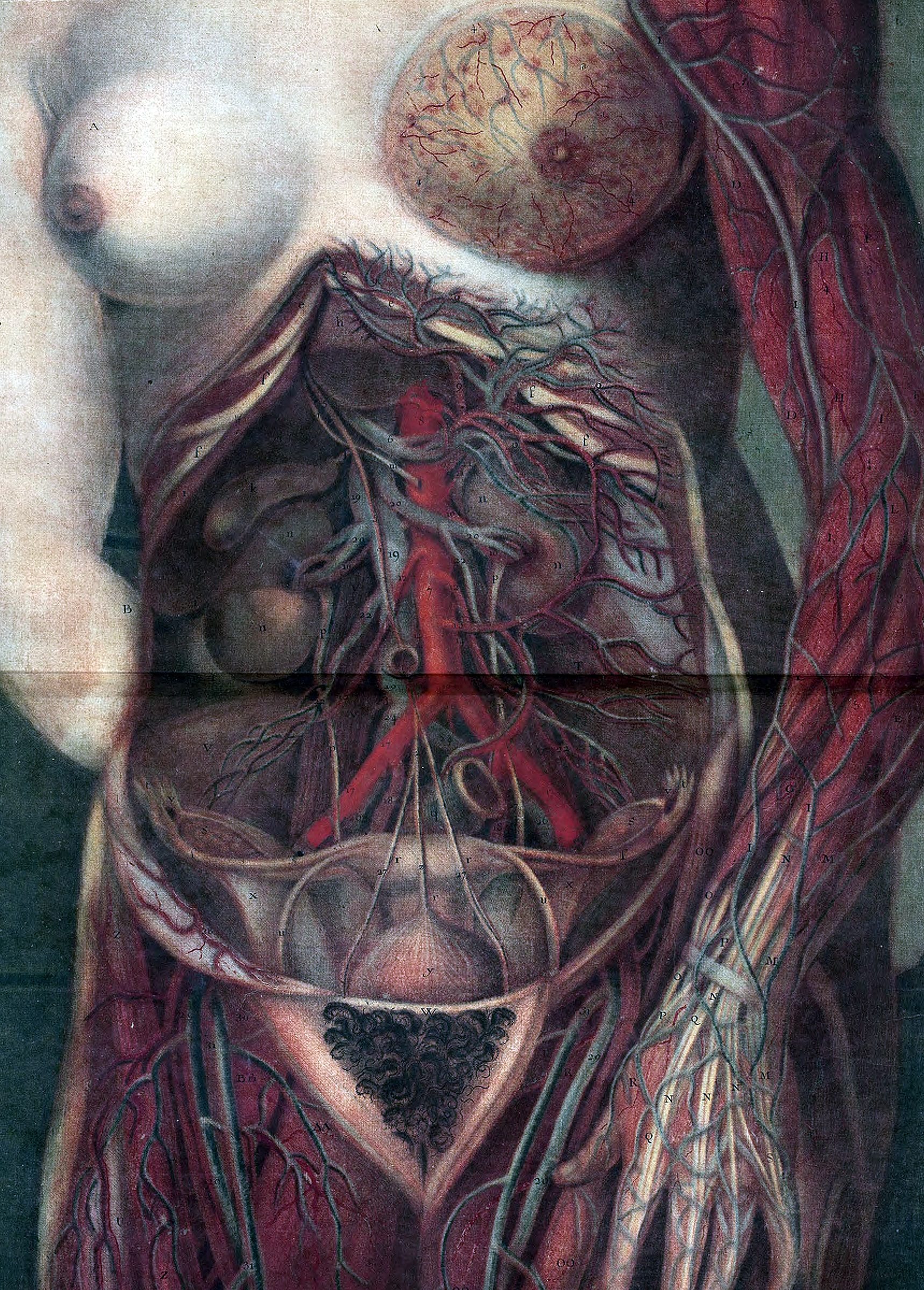

· Anatomie générale des viscères... (1752) – another major publication by the same author, also printed in color, focusing on the anatomy of the internal organs and the circulatory system.

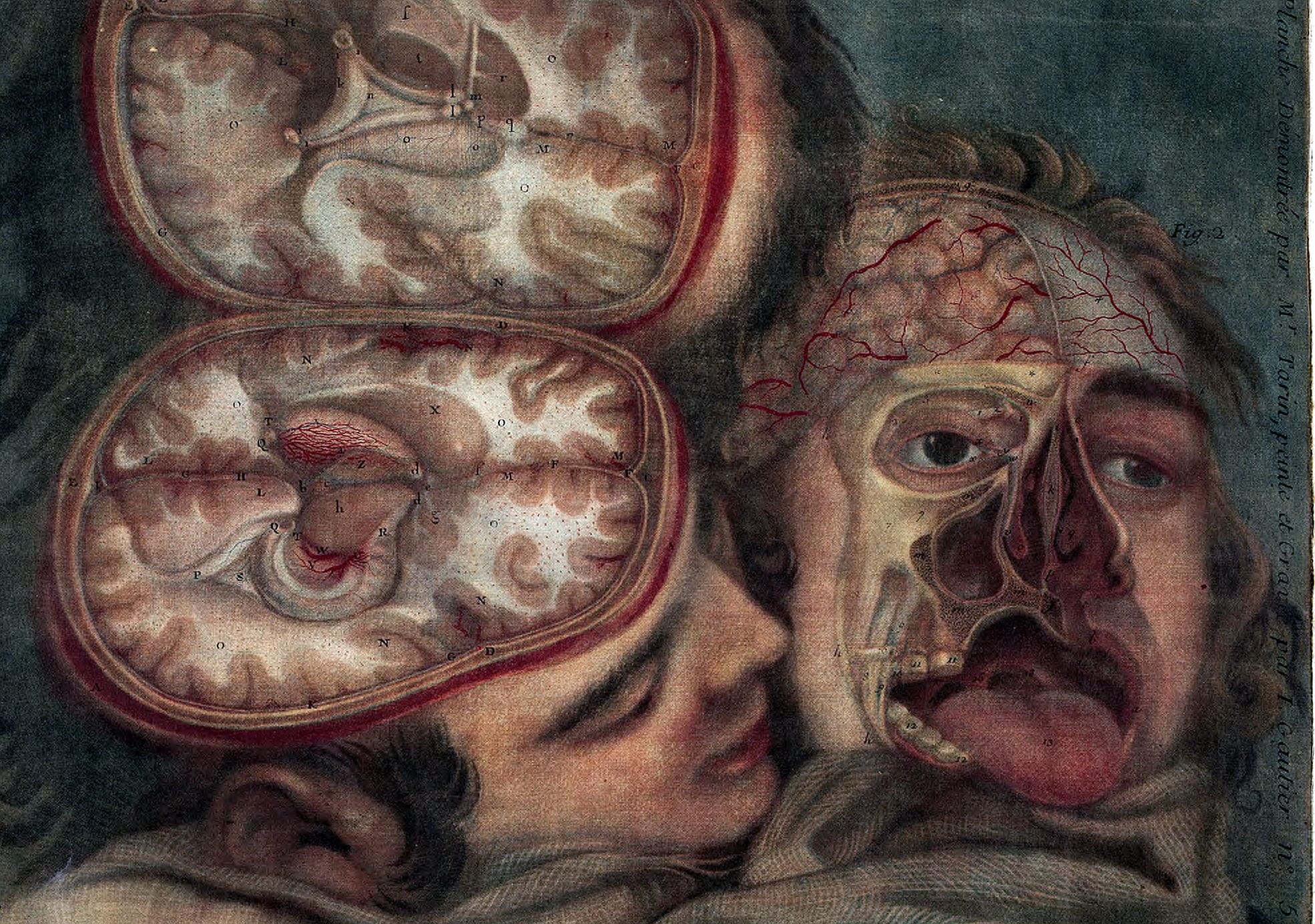

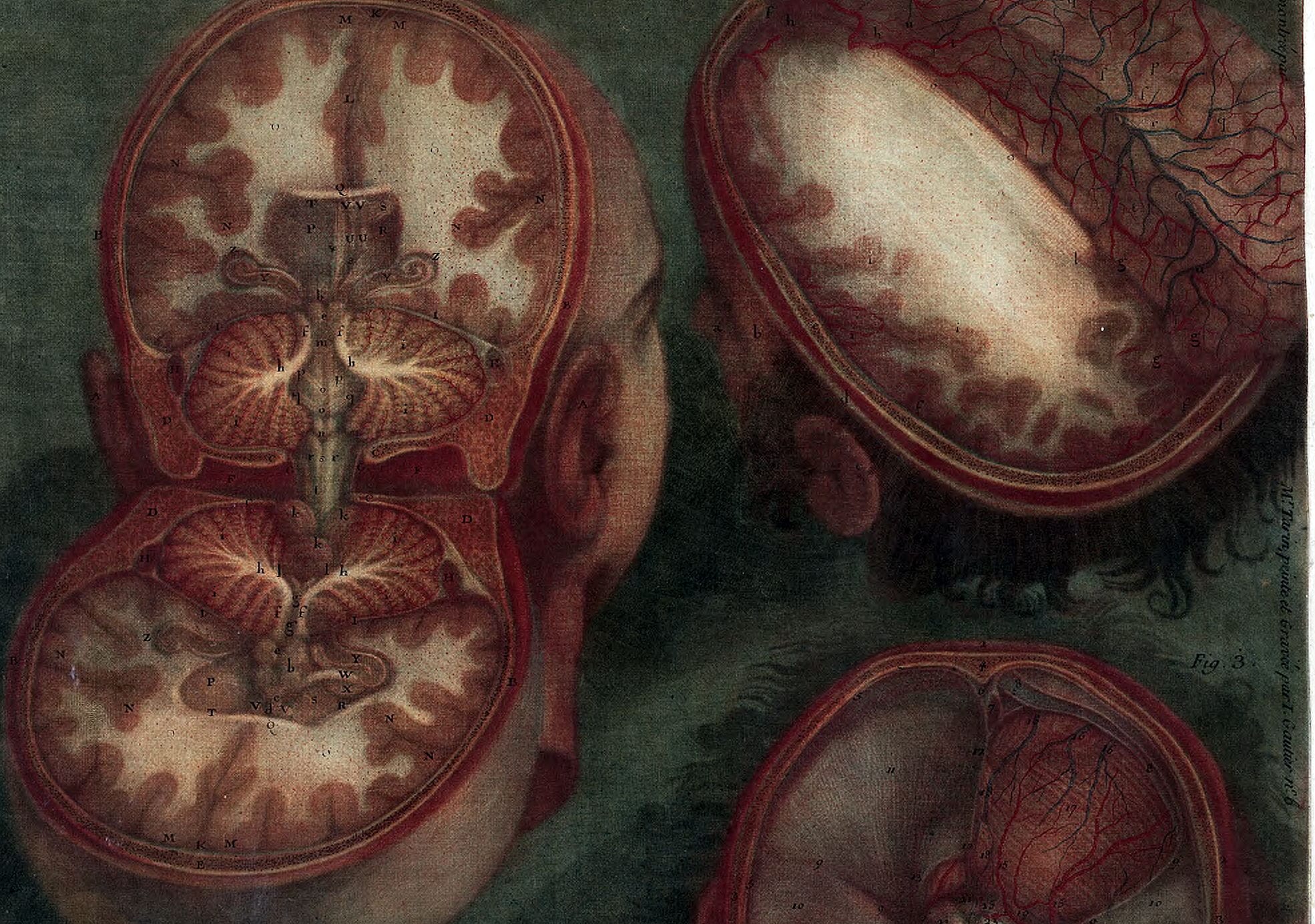

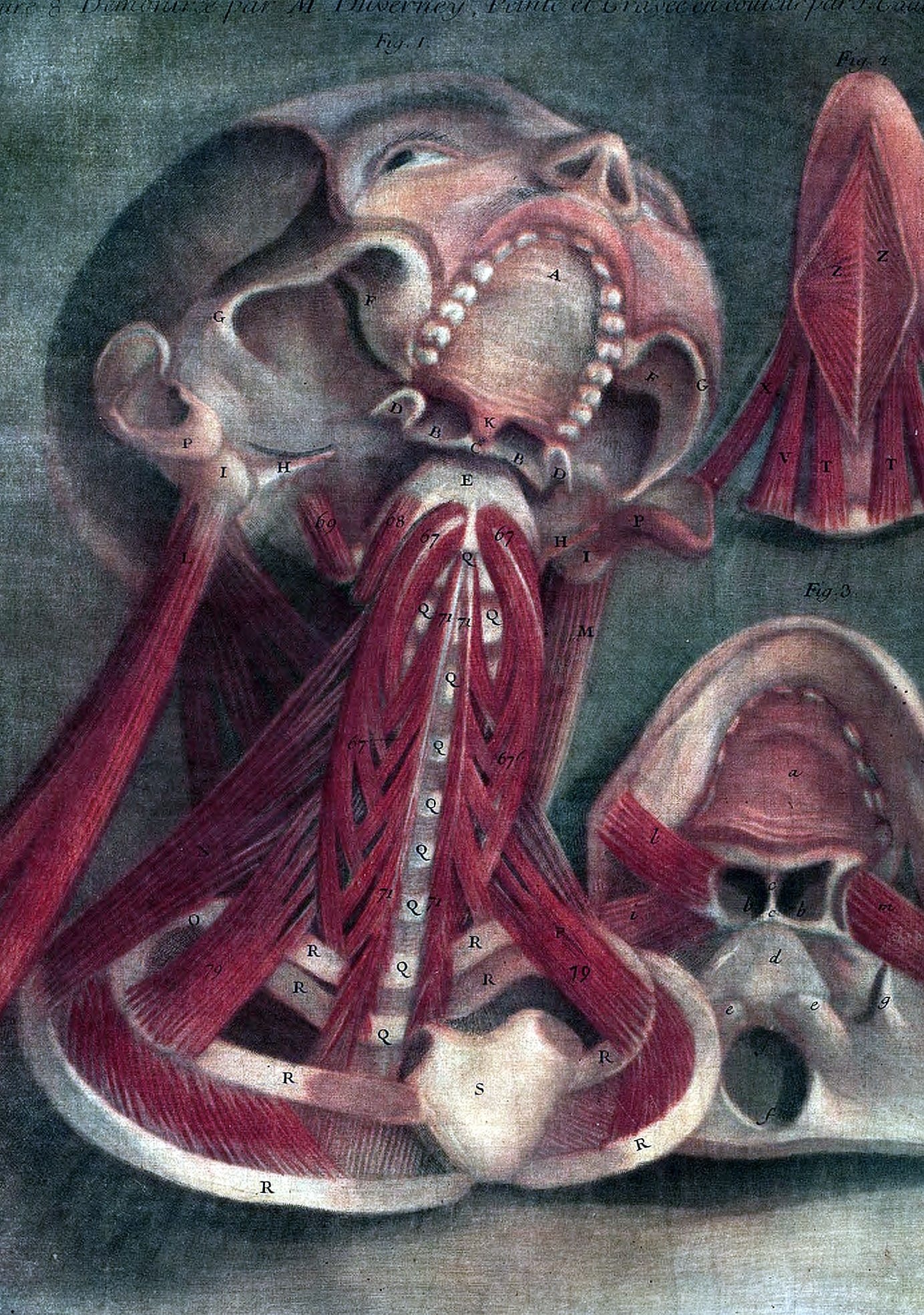

· Anatomie de la tête... (1748) – a study devoted to the head and brain, showing the organs of the senses and the distribution of blood vessels through detailed color plates.

Jacques-Fabien Gautier is born in Marseille in 1716. He grows up fascinated by painting — then by the possibility of printing images.

In 1736 he moves to Paris, chasing the scale that only big cities can offer. Two years later he joins the workshop of Jacob Christoph Le Blon, the pioneer of color printing under two royal privilèges from Louis XV. The job lasts six weeks. Gautier refuses to be an assistant and walks away.

When Le Blon dies in 1741, Gautier seizes the moment and claims his privilège—and with it, the title of inventor of color-printed pictures.

He starts by reproducing oil paintings, but soon turns to something new: scientific illustrations in color.

Eighteenth-century Europe is hungry for anatomy. Medicine is expanding, schools need images. Students must see veins and muscles clearly, yet hand-painted copies are costly and imprecise. Gautier’s method brings an industrial answer — the human body, printed in color, multiplied with precision.

Gautier and his five sons become influential figures in Paris’s artistic and printmaking circles, dominating the color-printing industry through the middle decades of the eighteenth century.

Taking the rights away from Le Blon’s heirs becomes one of the defining struggles of Gautier’s adult life. Once the privilège is his, he defends his title as the inventor of color printing with relentless determination.

Le Blon’s supporters argued that, in the 1730s, there were few French artists skilled in the mezzotint technique that formed the basis of tricolor printing — a shortage that limited his success.

Gautier dismissed Le Blon’s skill, seeing him as an artist misled by Newtonian theories.

In his own system, the foundation was reversed: black and white were the primitive colors, while red, yellow, and blue were secondary.

All five, he claimed, shared equal power in the creation of every other hue.

A selection of prints and wall pieces inspired by d’Agoty’s anatomical plates is available in our store:

Read more about Gautier in the full chapter of The Creation of Color in Eighteenth-Century Europe by Sarah Lowengard (Columbia, 2006) or download the full book for free.

If Zehnlicht’s books, films and soundfiction mean something to you, you can support the project by subscribing or with a one-time donation.

Subscribing starts at US$1 and is the easiest way to help keep the site independent and ad-free.

One-time donations are also welcome.